No, Castle Doctrine Does Not Increase Violent Crime

Debunking the misleading "study" gathering steam

with Second Amendment restrictionists.

![]()

by Howard Nemerov, July 11th 2013

Article Source

When George Zimmerman shot Trayvon Martin, anti-rights politicians and media saw an opportunity to sway public opinion in favor of repealing state "castle doctrine" laws. All they needed was supportive "research."

When George Zimmerman shot Trayvon Martin, anti-rights politicians and media saw an opportunity to sway public opinion in favor of repealing state "castle doctrine" laws. All they needed was supportive "research."

Enter Cheng Cheng and Mark Hoekstra, both of the Texas A&M University Economics Department — they published a paper titled "Does Strengthening Self-Defense Law Deter Crime or Escalate Violence? Evidence from Expansions to Castle Doctrine." They concluded that "castle doctrine" had no beneficial impact on burglary, robbery, and aggravated assault. They also claimed that the result of "strengthening self-defense law is increased homicide." Their conclusion: enhanced self-defense laws caused more murder.

The media ate it up. The Chicago Tribune ran an article titled "Report: 'Stand Your Ground' laws lead to increase in homicide." Think Progress, while covering Alaska governor Sean Parnell's signing of the state's new Stand Your Ground law, wrote: "Studies have shown that Stand Your Ground laws are discriminatory, associated with higher homicide rates, and don't deter crime."

Had the media actually explored available data themselves, Cheng and Hoekstra's research would have been marginalized instead of lauded as evidence that "castle doctrine" should be repealed.

What is "castle doctrine"?

"Castle doctrine" laws include three possible enhancements to existing self-defense laws. First: if people are someplace they have the right to be, they're no longer obligated to attempt flight before using defensive force (Remove Duty to Retreat, also called Stand Your Ground). Second: if attacked, it's reasonable for the defender to believe their life is at risk (Presumption of Reasonable Fear). Third: it's much harder for attackers or their estate to sue for damages resulting from justifiable self-defense (Civil Liability Protection).

Not all "castle doctrine" states enact all three enhancements, nor do they necessarily enact them all at once. For example, Alaska had already enacted the second and third enhancements prior to removing the duty to retreat.

Authors' dataset contains errors and inaccurate assumptions

Cheng and Hoekstra recently published an updated version of their research, yet the authors retained numerous errors from their earlier version, calling into question their methods and motives.

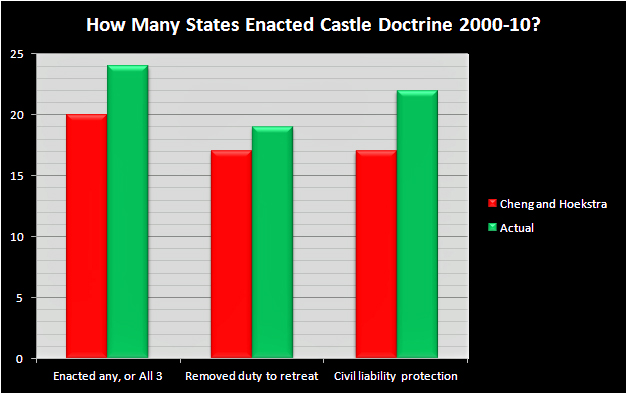

Cheng and Hoekstra compiled a table of 20 states that enacted some or all of these "castle doctrine" laws between 2000 and 2010, but 24 states enacted "castle doctrine" laws during their study period [page 36].

They claimed that Missouri enacted Stand Your Ground and civil protection, but Missouri law includes limited enhancements and shouldn't be counted. Even so, their dataset contained many other errors. For example, they claimed 17 states removed the duty to retreat during their study period — actually, 19 did. Twenty-two states provide civil liability protection — the authors included only 17 (see graph below). They correctly noted that 13 states enacted Presumption of Reasonable Fear, but they ignored four states that enacted "castle doctrine" laws: Idaho (2006), Maine (2007), Wisconsin (2008), and Wyoming (2008).

(Cheng & Hoekstra [page 7] cited National Rifle Association's Institute for Legislative Action, as did I)

Another problem with their dataset is that they equate Stand Your Ground with "castle doctrine":

In 2005, Florida became the first in a recent wave of states to pass laws that explicitly extend castle doctrine to places outside the home, and to expand self-defense protections in other ways. Since then, more than 20 states have followed in strengthening their self-defense laws by passing versions of "castle doctrine" or "stand-your-ground" laws. … For ease of exposition, we subsequently refer to these laws as castle doctrine laws. [page 1]

As shown later in this article, the difference between enacting only Stand Your Ground and full "castle doctrine" is significant when looking at crime trends.

The authors also assumed that enhanced self-defense laws deter non-confrontational crimes like burglary [page 2]. However, property crimes like burglary are more likely to increase when more citizens partake of their civil right of self-defense. In The Bias Against Guns, John Lott explained:

If you make something more difficult, people will be less likely to engage in it … just as grocery shoppers switch between different types of produce depending on costs, criminals switch between different kinds of prey depending on the cost of attacking. Economists call this, appropriately enough, "the substitution effect."

Instead of violent, confrontational crime like robbery to obtain a victim's property, criminals wait until victims leave home before committing burglary, which presents less personal risk to themselves.

FBI crime data support Lott's premise. As more law-abiding citizens arm themselves, violent crimes drop and property crimes rise. Of all FBI major crime categories, only burglary increased between 2000 and 2010 (over 5%). Meanwhile, homicide incidents decreased over 5%, robbery decreased 10%, and aggravated assaults decreased 15%.

Cheng and Hoekstra claimed they wanted to determine "whether strengthening self-defense laws deters criminals," but including burglary is simply an attempt to derogate "castle doctrine" for doing what it should: causing criminals to commit more property crimes and fewer violent crimes.

The authors altered their own conclusions by beginning with a misleading dataset.

FBI data show that "castle doctrine" correlates with less violent crime, not more

The authors attempted to guess what violent crime rates should have been had "castle doctrine" states not enhanced their self-defense laws by comparing them to non-"castle doctrine" states [page 3].

One way to determine if states benefitted from enhanced self-defense laws is to ask whether violent crime rates increase or decrease after enactment. If rates increased, then enacting "castle doctrine" laws created a "cost" because higher rates meant greater victimization. If rates decreased, then these laws created a "savings" because of less victimization after enactment.

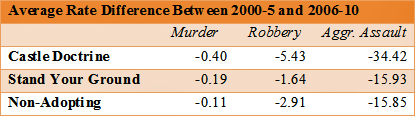

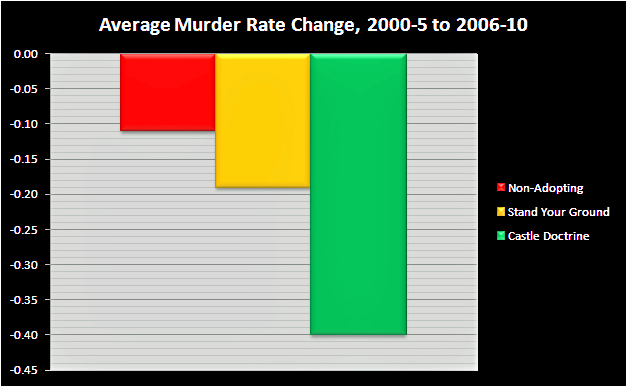

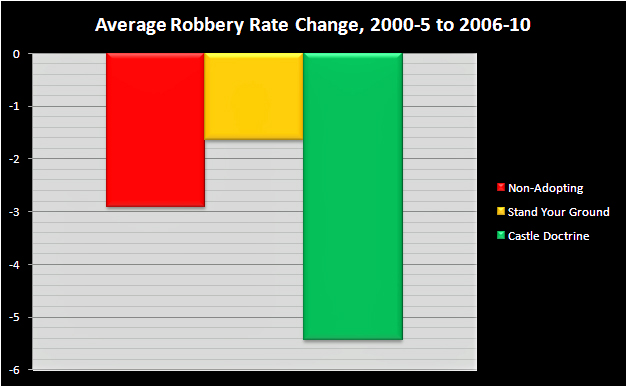

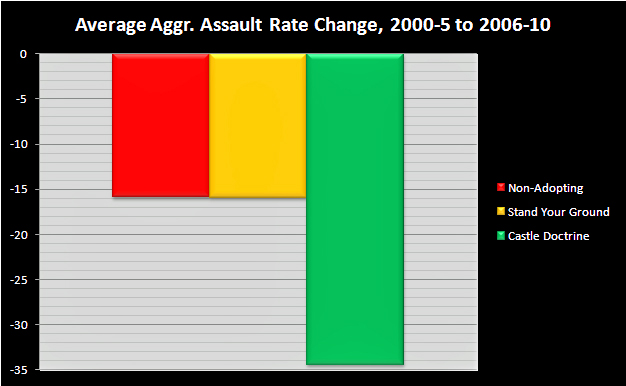

Averaging five or more years together gives a picture of the general level of violence during that time period. For the states in this study, the average year they enacted "castle doctrine" laws was 2006. Including non-enacting states' performance before and after 2006 provides a comparison to see how well states did without enhanced self-defense laws. This dataset includes "before" years of 2000-2005 and "after" years of 2006-2010. For Stand Your Ground and full "castle doctrine" states, their year of enactment defines "before" and "after" periods, each with their murder, robbery, and aggravated assault rates averaged. If the average crime rate was lower in the "after" period, the state became safer.

The truth? States that adopted all three "castle doctrine" laws experienced the largest declines in all three violent crime rates, handily besting non-adopting states.

Stand Your Ground states (removing Duty to Retreat but not necessarily Civil Immunity Protection and Presumption of Reasonable Fear) averaged larger decreases in murder rates than non-adopting states, too. While their aggravated assaults declined on par with non-adopting states, their robbery rates — while dropping after enactment — declined less than non-adopting states:

(All crime rates describe the number of victims per 100,000 population)

These data suggest that Cheng and Hoekstra had a point only if their sole conclusion highlighted the smaller benefits of enacting No Duty to Retreat laws alone. To claim that homicide increased is questionable at best.

Most importantly, Cheng and Hoekstra suggested these laws affect crime rates. If true, the data show adopting all three "castle doctrine" laws causes a noticeable decrease in violent crime.

Former civilian disarmament supporter and medical researcher Howard Nemerov investigates the civil liberty of self-defense and examines the issue of gun control, resulting in his book Four Hundred Years of Gun Control: Why Isn't It Working? He appears frequently on radio as an analyst and was published in the Texas Review of Law and Politics with professors David Kopel and Carlisle Moody.

![]()